Can tech fix crime like Ozempic did for obesity?

Blacktivists wield far more power than fat acceptance advocates

In 2021, the FDA approved a little-known diabetes medication called Ozempic for weight loss. Its success has decimated the fat acceptance movement and sparked hopes for tech-driven solutions to other tough social issues, like crime.

Genomics and data-science companies have made real breakthroughs in this space, but activists have successfully shut down many projects and stalled research. Once startups partner with law enforcement, funding dries up. The government has also clamped down on basic research with unfavorable racial implications.

There’s hope, but it’s distant. Without radical political change, scientists aiming to reduce crime need alternative infrastructure that can bypass government-aligned censors.

Blexit, Voice, and Loyalty

Crime is a key factor people consider when choosing where to live, and its impact can be measured through housing prices. For instance:

A 2010 study from Miami-Dade County found that a 1% rise in robberies and assaults leads to a 0.1% to 0.3% drop in property values.

A 2012 report across eight US cities suggested that a 10% reduction in homicides is associated with a 0.83% increase in housing values the following year.

However, focusing on prices alone underestimates the full impact of crime, largely due to price elasticity. In areas with an elastic (YIMBY) housing supply, prices may not immediately drop in response to rising crime. Instead, higher buying and selling activity and rising vacancy rates reflect residents’ decisions to leave, even as prices remain steady.

In the United States, this pattern of fleeing high-crime cities to low-crime suburbs began in the 1950s. The term “white flight” has often been used to suggest this suburbanization was driven mainly by antiblack avoidance. However, census data since the 1990s shows that well-off black Americans have also moved to the suburbs in significant numbers, leaving the cities to their dreg cousins and to recent immigrants. As Hanania writes in “Conservatives Are Lying on Immigrant Crime”:

In recent years, a great deal of the urban unrest we’ve seen has been set off by conflicts between black youths and immigrant store owners. Michael Brown was shot by a white police officer after robbing an Indian-American owned liquor store. In the moments before he died, George Floyd ended up in a confrontation with police because he tried to pass off a fake $20 bill to a Palestinian-American business. Even outside of the context of convenience stores and gas stations, immigrants living disproportionately in urban areas means that they are often more likely to fall victim to crime than other Americans.

Hanania drops this truth nuke: immigrants are more often the victims of America’s native-born criminal class. Conservatives, unable to influence policy enough to curb crime, have largely chosen to abandon high-crime areas. The frustrated conservatives then shift the blame to immigrants to satisfy their cultural and aesthetic biases.

Hanania surveys some international, actually-effective solutions to crime: Bukele’s “iron fist” approach in El Salvador, which focuses on harsher enforcement, and Denmark’s surveillance of repeat offenders through DNA databases. The tone shifts to pessimism when he discusses the domestic use of anti-crime technology, particularly how black activists dismantled ShotSpotter in Chicago in 2024.

Can technological innovation find ways to bypass the barriers created by activists trying to shield “communities” from accountability?

Somebody’s doing the shooting

ShotSpotter began as an engineer’s side project in 1992, aimed at triangulating the location of gunshots using differences in timing between three acoustic sensors. A major challenge was that police departments struggled to act on the data. When officers were dispatched but found no evidence, both internal and external critics were quick to blame the technology itself.

The pattern behind the deployment of this technology is that it’s sold on the promise that machines are less biased than police officers. What leftists hope for is that this will mean fewer black Americans facing prosecution and incarceration. However, “equity”-based concerns like this clash directly with the evidence that new technology gifts us that tells us who exactly is doing the shooting.

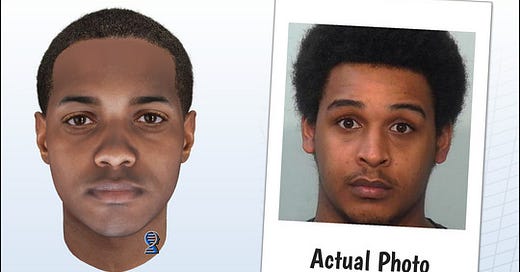

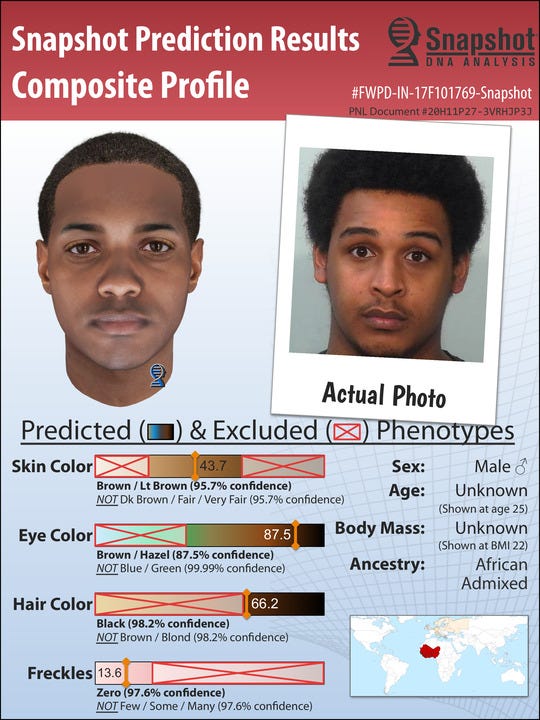

Parabon NanoLabs is one company in the CrimeTech space that provides phenotype reports that can sketch a person’s appearance based on a DNA sample. This forensic genetic genealogy advanced despite restrictions from direct-to-consumer companies like 23andMe or Ancestry.com, which prohibit law enforcement use.

Political barriers mounted after the high-profile 2018 case in which forensic genealogists helped identify the “Golden State Killer”. Buzzfeed-led activism pushed DNA data providers, including GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA, to limit law enforcement access without explicit user consent.

But “privacy” and “consent” are just a smokescreen for the real target—in the words of the US government’s National Institutes of Health (NIH), “stigmatizing research”. The NIH denies access to genomic data to researchers who aim to study differences between human groups, like the relationship between race and intelligence.

Science outside the cathedral

In the U.S., the federal government funds 40% of basic research, more than any other source. This means both funding and data access is conditional on avoiding research results that could be viewed as unfavorable to black Americans. These restrictions also limit the development of CrimeTech products that could help solve cold cases or reduce homicides.

I salute the scientists who stay within established institutions and voice their protest against restrictions designed to protect certain racial groups from unfavorable research. But like the non-criminal residents who fled cities during the rise of urban crime, the cause—the “city”—may already be lost. Truth-seekers need new infrastructure, a fresh start in a different space, if they are to flee to new frontiers.

One possibility for the new “suburbs” of scientific inquiry is the DeSci (Decentralized Science) movement. Though still in its early stages as of 2024, DeSci offers a chance to better align the incentives of its research and its funders. Distributing data across the blockchain can also better protect against attacks like the activists’ on the centralized genealogical databases.

Freedom isn’t free, and supporting unrestrained scientific inquiry is vital. You can invest in forensic or surveillance companies like those which I’ve mentioned here (I have no positions to disclose), or contribute to building new infrastructure, like Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) in DeSci. In the cat-and-mouse game between scientists and censors, cats need to keep building.