Haiti, the Génocidaire's Republic

And the long American tradition of running interference for it

When discussing illegal immigration to the United States, handshakeworthy restrictionists prefer focusing on countries like Venezuela or Guatemala over Haiti. This doesn’t make much sense when you quantify the impact—take the infamous city of Springfield, Ohio, where fatal car crashes spiked fourfold between 2022 and 2023.

The reluctance to engage with Haiti becomes clearer when you understand it as more than just a country. To its defenders, the Republic of Haiti symbolizes something bigger. Matt Yglesias illustrates this indirectly, noting that to criticize a majority-Black country (in his example, Jamaica) quickly leads to accusations of racism:

If you hear about someone who really hates Israel, “maybe she hates Jews” is a plausible hypothesis since Israel is, after all, the Jewish state. But there’s only one Jewish state, so it’s a hard hypothesis to test. If someone hates Jamaica and stands accused of hating Jamaica for racist reasons, he could counter with demonstrated affection for the Bahamas or another majority-Black country. But Israel is unique, so how would you know?

Just as Matt argues that Israel is unique, I’d say the same for Haiti—but not in the usual sense of it being a republic born from a glorious slave revolt! Haiti’s true uniqueness lies in its racialist (Black supremacist) political culture and the centuries of foreign apologia surrounding its atrocities.

Snow Bunny Nationalism

The 1805 Constitution of Haiti made two notable exceptions to its ban on ‘white men’ owning land. The first, more famous exception, accommodated the 240 Polish soldiers (from the 5,200 Napoleon sent) who defected. Despite enthusiastic efforts, no trace of these Polish descendants has been found.

The idea of righteous whites shielded by benevolent Black revolutionaries has strong propaganda appeal. But contrast that myth with the grim reality in towns rumored to have Polish heritage, where lighter-skinned residents lived. In 1969, the Tonton Macoute—Haiti’s secret police, named after a figure from voodoo folklore—set homes ablaze, raped residents, and massacred dozens of peasant families in Cazale.

The lighter-skinned residents likely stem from the second exception in Dessalines’ constitution, which granted land rights to white women married to Black men and their mixed-race descendants. These families, despite persecution, managed to gain influence in sectors like commerce, which were less tied to government control.

The Lightskin-Darkskin Dialectic

Haitians with European ancestry have a “mixed” political and military record. After Dessalines’ assassination, the north was ruled by an anti-mulatto regime, while the south was more mulatto-tolerant. By 1820, the south conquered the north and soon occupied the newly independent Dominican Republic.

The justification for this aggression? Jean-Pierre Boyer, Haiti’s second president, framed his invasion of paler Dominican Republic as a generous offer of “Black liberation”. In a pattern that we see over and over in the history of Haiti, black elites respected no distinction between foreigners and natives with European ancestry.

Even as late as 1957, the soon-to-be dictator, ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, launched a racialist campaign against mulattoes under the banner of noirisme. Scapegoating ‘whites’ persisted, even though the last significant infusion of European ancestry (from the Poles) was a distant memory.

We Live in the Context

Let me break the fourth wall for a moment to complain about how difficult it is to research Haiti’s history when you are trying to say something fresh, rather than joining the usual problack call-and-response. For instance, when I was double-checking dates for Haiti’s invasion of the Dominican Republic—a LLM directed me to “Blackpast”, a website whose tendentious mission is to “reclaim and restore the stories of those within Black communities whose voices have long been marginalized”.

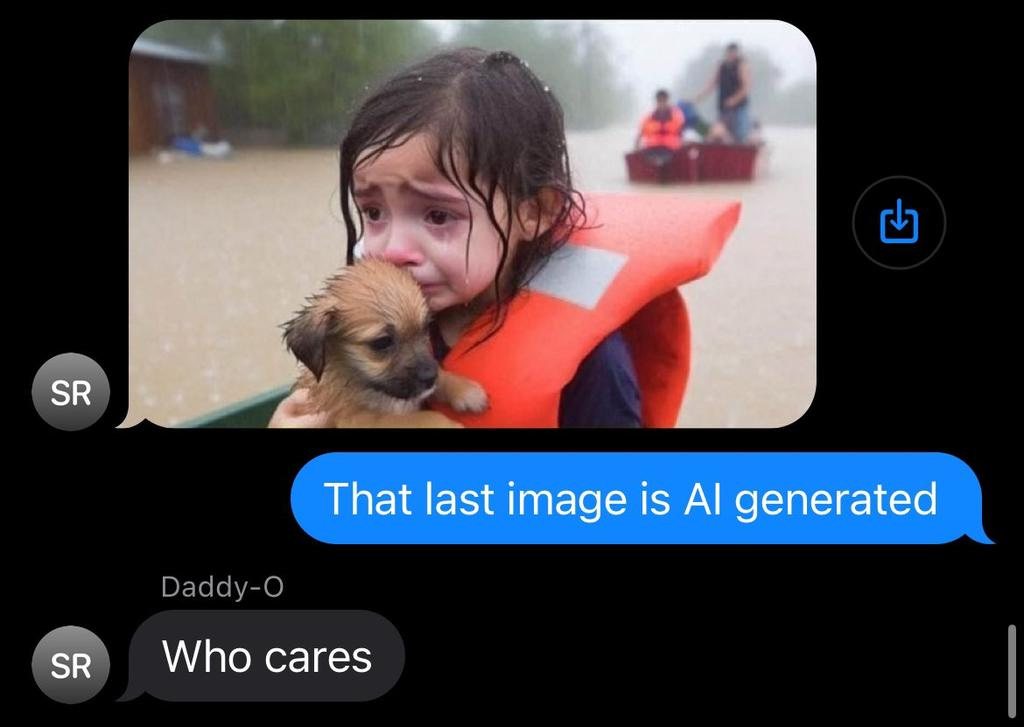

Now try Googling the recent cat-eating scandal from Ohio, and you’ll sift through a thousand ‘debunker’ articles before you find any real investigative journalism. The typical ‘fact check’ playbook (more about narrative than facts) works like this:

Premise: Reports of Haitian wrongdoing ‘dehumanize’ Haitians

Addendum: Haiti and Haitians represent freedom and Black liberation

Conclusion: Therefore, the reporters must have bad intentions—and must be liars

Historical Whitewashing

This motivated misrepresentation of Haiti is over a century old. In 1920, James Weldon Johnson, executive secretary of the NAACP, published an article titled “The Truth about Haiti”, which inverted the country’s reality at the time. Johnson portrayed Haitians as exceptionally law-abiding, hardworking and racially unprejudiced:

The absence of crime in Haiti is remarkable, and the morality of the people is strikingly high. Port-au-Prince is a city of more than 100,000, but there is no sign of the prostitution that is so flagrant in many Latin-American cities. I was there for six weeks and in all that time, not a single case of a man being accosted by a woman on the street came to my attention. I heard even from the lips of American Marines tributes to the chastity of the Haitian women. […]

The Americans have carried American prejudice to Haiti. Before their advent, there was no such thing in social circles as race prejudice. Social affairs were attended on the same footing by natives and white foreigners. The men in the American Occupation, when they first went down, also attended Haitian social affairs, but now they have set up their own social circle and established their own club to which no Haitian is invited, no matter what his social standing is. The Haitians now retaliate by never inviting Americans to their social affairs or their clubs. […]

The United States has failed in Haiti. It should get out as well and as quickly as it can and restore to the Haitian people their independence and sovereignty. The colored people of the United States should be interested in seeing that this is done, for Haiti is the one best chance that the Negro has in the world to prove that he is capable of the highest self-government. If Haiti should ultimately lose her independence, that one best chance will be lost.

The NAACP’s narrative painted Haiti as a near-paradise corrupted by the arrival of exploitative Americans—a framework that communists later used to defend Castro’s Cuba. In Johnson’s time, however, this narrative of Haitian innocence and industry was framed as proof of the Negro’s ability for ‘self-government’.

Run It Back Turbo

What about today’s information environment? On one side, the government, media, and academia continue to carry the torch of Haitian apologia. On the other, anyone can now watch up-to-date, unfiltered travelogues by regular people—like Drew Binsky’s 30-minute film from last year, revealing a level of cruelty, disorder, and filth that has no contemporary parallel.

Yet, Binsky’s YouTube description still reads: “My heart aches for the people in Haiti, who are living through this disastrous situation.” Even the filmmaker, personally threatened by a Haitian gang member on camera, seems to deny his tormentors any agency. Talk about a powerful narrative frame!

Simply uncovering more facts about Springfield or Charleroi won’t stop centuries-old racialist scams. Focusing on Haitian deprivation without understanding how the country got there—through sustained violence against its economically productive nonblack or lighter-skinned communities—will always risk being dismissed as “punching down”.

The new story that needs to be told about Haiti’s perpetual revolution is one of relentless scapegoating and violence against foreigners who arrived with naive but well-meaning intentions. As long as this story remains untold, we will repeat history—not just in Haiti, but also in South Africa, Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, and other such cases.