A few days ago, I fell down a TikTok rabbit hole about the murder of Lakan Riley by Jose Ibarra.1 Modern surveillance tech offers a cornucopia of “content” for true crime enthusiasts around this case, from the timestamps of Riley’s final text messages to her mother, to the exact second her smart watch recorded her heart rate drop to zero. From fear to rage, the comments sections were a battleground of women’s voices.

To me, they might as well have been speaking a foreign language. My approach to politics is more autistic, objectifying problems through number-crunching and Bayesian “updates” to my “priors” derived from statistics. But as Brian Chau discovered during his journey from AI engineer to DC lobbyist, this rationalist mode, rooted in technical rigor, is not only boring but also fundamentally unpersuasive:

I stumbled into a role advocating for informed AI optimism, the idea that the underlying evidence from technical and historical precedent weighed vastly in favor of AI benefits than harms. […] But I quickly discovered that bringing up those statistics would make people’s eyes glaze over. They wanted drama, political relevance, and grand narratives. I learned that no one believes in AI doom because of definite factors of production. They all believe in AI doom because of stories and hypotheticals. That made my theory of change mostly irrelevant.

A familiar sense of horror washed over me as I read Bruce Gilley’s 2023 book The Case for Colonialism. On one side, scholars labor to fortify the historical record with serious cost-benefit analyses of colonialism’s impact on health, education, and economic outcomes. On the other side, ritualistic invocations of “evil” and “harm” smite journal articles into instant retraction. Which side dominates the discourse space?

In any case, the world we live in today is far removed from the caricature Gilley highlights of “white men with upturned mustaches and pith hats making pompous statements about the need for order.” The astronomical postcolonial divergence between Africa and Asia has shattered the “black and brown” coalition, raising the salience of new stories—like the one I want to tell about the tragedy of Zanzibar.

Arabs and Persians and Indians, Oh My!

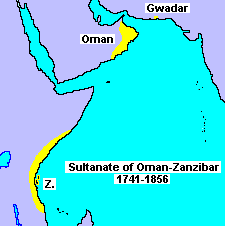

Zanzibar, an island off the coast of East Africa, carries a curiously Perso-Arabic name. Its present-day Bantu overlords in Tanzania call it “Unguja,” but the only people for whom this stings are a few refugees’ descendants in Oman. British gunboats claimed the island for the Queen in 1896, but their rule left the racial balance intact: unlike in Rhodesia-Zimbabwe or Fiji, they did not import large numbers of whites or Indians.

Zanzibar was already a multiracial society, thanks to the low time preference of the Omani Arabs, who established clove plantations in the 1820s. Gujarati merchants soon joined the party, offering financial and trade intermediary services. Before the genocide of 1964, Zanzibar’s population reflected a three-part racial division: black Africans2 numbered 230,000 (76%), Arabs 50,000 (17%), and South Asians 20,000 (7%).

Yes, some Arab landowners did a little penny-pinching on wages for their clove-pickers—under constant harassment from the British, who called this “slavery.” But the same moral stain cannot be applied to Zanzibar’s South Asian residents, whose wealth came from a far more diversified portfolio. From retail and customs collection to wholesaling, Asian prosperity was built on commerce, not coercion or exploitation.

The subcontinental traditions represented on the island were diverse, including Hindu Banias, Shia Khojas, and Sunni Memons. What united them was a shared understanding that profits were to be reinvested into productive ventures or credit networks. Their resentful black customers in the duka (दुकान) shops, by contrast, spent their earnings on flashy consumer goods such as wristwatches, bicycles, and radios.

When Black kills Brown and Beige

These radios began delivering “Hutu Power Radio”-style terror in January 1964, as islanders tuned into puzzling daily broadcasts by self-styled “Field Marshal” John Gideon Okello. A Ugandan with no ties to Zanzibar, Okello issued bizarre, innumerate threats, starting with: “We, the army have the strength of 99 million, 99 thousand.” Outside analysts like the CIA struggled to gauge how seriously to take him:

For days, the flow of Okello’s inflammatory words issued forth constantly from the Zanzibar radio station. Even in the face of a denial by [Zanzibar’s post-British President] Karume that members and supporters of the overthrown regime would be executed, the Field Marshal kept repeating his frightful threats that he would “cut up into pieces” all the Asians who did not surrender their weapons—or else “throw them into the sea” or “burn them alive after having sprinkled them with gasoline” or “transform them into living targets for shooting practice.”

Okello was actually able to fulfill this prophecy because Zanzibar had no standing army—only a police force, which became the first target for his 330 armed men who sailed from mainland Africa. After neutralizing the police, Okello’s forces fanned out across the island to kill Arabs and Asians, mutilate their bodies (including putting male victims’ genitals in their mouths), and parade them through the streets.

Despite later apologia framing Okello as a champion of local grievances, both he and his forces were alien to the island in culture and origin. John “Gideon”, a Christian visitor to an overwhelmingly Muslim island, directed his forces to loot and burn Arab mosques and destroy Hindu temples. Gilley tallies the demographic and economic devastation of this “revolution”, launched one month after the British departure:

A U.S. diplomat stationed on the island described black gangs going house to house with machetes. An Italian film crew recorded the blood-letting from the air. Only 1 in 10 of the criminals who took part in the revolution were from Zanzibar, despite attempts to portray it as a local uprising against local legacies. Over just two days, between 5,000 and 10,000 people were murdered. A further 20,000 “stooges” were imprisoned, while 100,000 mostly middle class and wealthy people fled the island—so 43% of the population was either killed, imprisoned, or exiled.

The Strategic Logic of Sparing Whites

The violence orchestrated by the Ugandan genocidaire was not the chaos of a spontaneous race riot. Okello issued precise orders: Arab men aged 18 to 55 were to perish first; the wives of detained men were not to be violated; and whites were to be spared entirely. Europeans and Americans were swiftly evacuated to British-ruled Mombasa, allowing Okello to successfully avoid provoking international intervention.

Did this Tropical Napoleon have reason to fear that mass killing of whites would be a red line for the British or Americans? Perhaps John Okello learned this lesson during his early adulthood in Kenya. While serving time for rape, he witnessed the Mau Mau provoke a fierce British crackdown after newspapers splashed photos of bloody teddy bears from the rebels’ slaughter of white settler families like the Rucks.

A contemporaneous crisis in the Congo reinforced the point that, sometimes, White Lives did Matter. The formerly Belgian Congo, independent since 1960, had spent years in an orgy of black-on-black violence, as postcolonials debated the merits of communism with machetes. But in 1964, when one faction escalated by taking foreign nationals hostage, Belgian paratroopers intervened, airlifting 1,000 of them to safety.

Elsewhere in Africa, nonblack populations who escaped the slaughter of the High Soviet period merely bought themselves a few decades. In South Africa and Rhodesia, the colonial metropole had washed its hands of responsibility in 1961 and 1965. Ultimately, those farm invasions and massacres that were completed in Eastern Africa were simply deferred in Southern Africa until the 1990s post-apartheid celebrations.

Who wears the pith hats now?

Nick Land once mused that “cheap cotton was the most expensive product in the history of the earth.” For the Arab and Asian ghosts haunting Zanzibar, cheap cloves are no less bitter a crop. Across the dark continent, black racial resentment levies its blood tax on sojourner communities daring to trade or invest—from the Lebanese in Côte d’Ivoire to the Chinese in Zambia. Is the risk worth the reward?

Decades of postcolonial failure in Africa have dulled the appeal of blaming whites for plundering black wealth. The paradise promised by revolutionary terror never came. Zanzibar’s history unlocks a clearer truth: brown and beige wealth owed nothing to “structural racism” and everything to thrift, prudence, and temperance—virtues embodied by Asian shopkeepers who, in the end, sold the rope that hanged them.

The Lakan Riley case has become an American right-wing cause célèbre because Jose is an undocumented Venezuelan national. At an object level, I find the fixation on stories of mestizo men murdering white women frustrating, as it feeds into an “immigrant crime” narrative riddled with statistical falsehoods (particularly vis-à-vis the third rail of black crime). This post, however, focuses on the meta-level importance of emotional resonance.

Some Africans with deeper roots on the island than recent mainland arrivals identified as “Shirazi” (after a town in Iran), but this was just status-grubbing tied to Islam’s prestige, as modern genomics debunks any claim to Persian ancestry among 20th-century islanders.